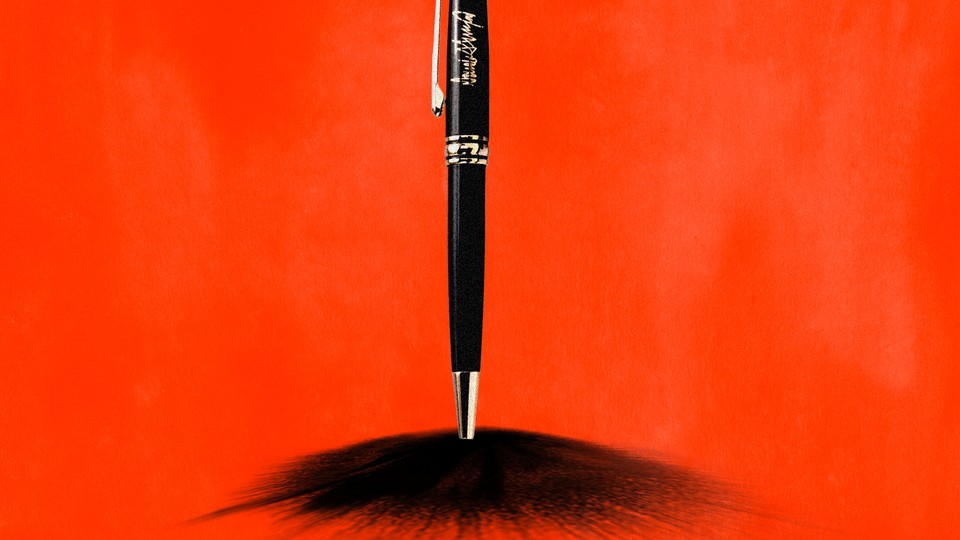

Trump’s Reasonable—And Yet Still Worrisome—Emergency Declaration

Americans must be alert to abuse of the president’s powers, both emergency and nonemergency, in ways that violate civil liberties without safeguarding the public’s health.

When President Donald Trump issued emergency declarations in response to the coronavirus pandemic on Friday, many Americans didn’t know whether to breathe a sigh of relief or to call the American Civil Liberties Union. Trump’s negligence in addressing the growing crisis had been galling to watch. But when a president with autocratic tendencies invokes emergency powers, red flags start to wave. Should Americans be encouraged by the president’s action—or deeply worried?

The coronavirus pandemic is clearly an emergency, and the emergency measures that Trump announced fall well within the law. They could give a moderate boost to efforts to treat the virus. But the declarations do not necessarily signal a newfound commitment to responsible disease-mitigation efforts, let alone undo the damage his neglect has caused. And given this president’s record of disdain for the rule of law, the country must be on guard for abuse of the president’s powers, both emergency and nonemergency, in ways that undermine civil liberties without advancing public health.

Let’s start with Friday’s declarations themselves. To assess whether they were appropriate, we need to know what powers Trump invoked, what they allow, and how he proposes to use them. After all, Congress has passed hundreds of laws that confer emergency powers, and they vary widely in the scope of the authorities they delegate and in the powers’ potential for abuse. Trump’s declarations Friday relied on two of these laws: the Stafford Act and the National Emergencies Act.

The Stafford Act, a 1988 law that amended the 1974 Disaster Relief Act, authorizes the president to declare either a “major disaster” or an “emergency” for the purpose of providing assistance to state and local governments whose resources have been overwhelmed. In this case, the president declared an emergency, but he also announced that he considered the coronavirus to meet the law’s definition of a “major disaster,” and invited states’ governors to request that he issue major-disaster declarations.

The definition of major disaster is fairly limited: It is confined to natural catastrophes, fires, floods, and explosions. The definition of emergency is much broader—“any occasion or instance for which, in the determination of the President, Federal assistance is needed to supplement State and local efforts and capabilities to save lives and to protect property and public health and safety, or to lessen or avert the threat of a catastrophe”—but some types of assistance available under a major-disaster declaration are not available under an emergency declaration. For either type of declaration, the Federal Emergency Management Agency is the responsible agency, and the source of funding is the Disaster Relief Fund—which currently contains more than $40 billion.

Under a Stafford Act emergency declaration, the federal government can perform various activities to support state and local emergency assistance. It can coordinate disaster-relief efforts, provide technical and advisory help to state and local governments, provide grants to individuals and households for temporary housing and personal needs, and distribute medicine and food. Under a major-disaster declaration, the federal government can provide additional forms of assistance—most notably, direct relief to victims and communities affected by the disaster in the form of unemployment assistance, food coupons, legal services, grants to assist low-income migrant and seasonal farmworkers, emergency public transportation, and emergency communications.

Even though a pandemic could clearly meet the Stafford Act’s definition of an emergency, using the law for such a purpose is actually quite unusual. Rather, federal responses to such crises generally take place under the auspices of the Department of Health and Human Services, using authorities provided by a different law, the Public Health Services Act (PHSA). In fact, a president has declared a Stafford Act emergency to address an outbreak of disease on only one prior occasion: In 2000, President Bill Clinton issued Stafford Act declarations in response to requests from the governors of New York and New Jersey to address an outbreak of the West Nile virus. No president has ever declared a major disaster in response to a health epidemic.

The other law on which Trump’s Friday declarations relied, the 1976 National Emergencies Act (NEA), represents an entirely different and far more dangerous model of emergency powers. The law itself confers no emergency authorities, but rather authorizes the president to invoke special powers contained in more than 100 other provisions of law, by virtue of declaring a “national emergency.” Unlike the Stafford Act, the NEA does not define what constitutes a qualifying emergency; that decision is left to the president. In the declaration, the president must specify which powers he intends to invoke, and he must issue updates if he adds new powers to the list.

The powers available to the president when he declares a national emergency touch on almost every area of government: agriculture, the economy, national defense, law enforcement, public health, and more. Many of the powers are targeted in scope, reasonable in what they seek to achieve, and not particularly susceptible to abuse—for instance, a provision allowing the secretary of transportation to waive vehicle weight limits for bulk shipments of jet fuel to an Air National Guard base. Others, however, are alarming. There are laws that enable the president to shut down or take over radio stations, freeze Americans’ bank accounts, unilaterally limit international trade, and detail U.S. forces to other governments. And the NEA has no requirement that the powers the president invokes relate to the nature of the emergency.

Very few of the powers that become available in a national emergency relate to matters of public health, and none of those powers provides access to funding. Accordingly, health crises in the United States do not usually trigger national-emergency declarations. However, one emergency power, contained in the Social Security Act, is available only if two emergency declarations are in place: a public-health emergency (under the PHSA), and either a Stafford Act emergency or a national emergency (under the NEA). This particular power allows the secretary of health and human services to waive certain Medicare, Medicaid, and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) requirements—for instance, a requirement that doctors be licensed in the state where they are practicing, rather than in another state with equivalent licensing standards—in order to facilitate the flexible delivery of health-care services. In order to invoke that provision, the Obama administration declared both a public-health emergency and a national emergency during the H1N1 pandemic in 2009.

According to his news conference on Friday, Trump intends to use the Stafford Act emergency declaration and the national-emergency declaration, in combination with the public-health-emergency declaration issued by Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar on January 31, to invoke the emergency-waiver provision of the Social Security Act and to loosen regulatory restrictions on the provision of health-care services. Specifically, the administration will ease constraints on the practice of telemedicine; waive provisions that limit the number of beds in critical-access hospitals to 25, and the length of stay to 96 hours; allow admission to nursing homes without a prior three-day hospital stay; and make it easier for hospitals to hire additional doctors, acquire new office space, and move patients within their facilities. (Trump also announced a series of other measures, mostly relating to public-private partnerships to speed the manufacture and distribution of test kits, but these are not being undertaken pursuant to emergency powers.)

Overall, this course of action is a sensible one, and does not in itself set off alarm bells. Public-health experts have warned that the greatest danger the country faces from this coronavirus is the likelihood that the American health-care system could become overwhelmed. These emergency measures could help to alleviate that outcome. They are designed to increase the capacity of hospitals by allowing them to acquire more beds and more physicians, while reducing the number of people in those hospitals by providing alternatives in the form of nursing homes or telemedicine.

Moreover, the potential for abuse seems low, at least for now. The Stafford Act defines what can constitute a major disaster or an emergency, and while it gives the federal government a significant amount of authority, that authority must be exercised in the service of specified disaster-response activities. None of the activities the president has identified go beyond what the law would allow.

As for the NEA, it is certainly subject to abuse as a general matter; it does not define national emergency, and it gives the president access to formidable powers. In this case, however, a real emergency clearly exists. In addition, the only power the president invoked under his national-emergency declaration is the Social Security Act waiver provision, which is not the type of power an authoritarian could readily exploit. In theory, Trump could later decide to add any of the other powers available during a national emergency—but he could do that already, under the national emergency he declared in February 2019 to build the border wall, or any of the 33 other national emergencies currently in place (many of which date back decades).

That’s not to say that the president’s actions give no reason for concern. For one thing, a president normally can issue a Stafford Act declaration only at the request of a state’s governor, and the assistance then goes only to that state. However, for emergencies (but not major disasters), the president can act without a governor’s request:

[W]hen he determines that an emergency exists for which the primary responsibility for response rests with the United States because the emergency involves a subject area for which, under the Constitution or laws of the United States, the United States exercises exclusive or preeminent responsibility and authority. In determining whether or not such an emergency exists, the President shall consult the Governor of any affected State, if practicable.

This is the path Trump took, declaring a “nationwide” Stafford Act emergency on the grounds that he was acting in an area of primary federal responsibility. There is no indication that he consulted every state’s governor before doing so, as the law directs.

That’s a major red flag. Aspects of the coronavirus response would certainly fall under federal auspices. The federal government clearly has power to regulate international travel, as well as interstate travel and commerce. But under the U.S. Constitution, the authority to make and enforce laws relating to public health and safety falls squarely within the powers of the states under the Tenth Amendment. That is true regardless of whether the particular health and safety issue is also faced by other states—after all, every state experiences illness and crime. Although the federal government has assumed increasing responsibility for public health in the past few decades, characterizing domestic disease-mitigation efforts as an area in which the federal government “exercises exclusive or preeminent responsibility and authority” is plainly wrong.

In this instance, the practical effect of the overreach is probably minimal, as states likely would have come forward with requests for Stafford Act declarations in the near future. But there is a context we cannot ignore: Trump’s pattern of contempt for the rule of law and claims of presidential authority that go far beyond what the law gives him. This is a president who asserts that Article II of the Constitution allows him to do “whatever I want to do,” who orders federal officials not to comply with congressional subpoenas, and who describes as “perfect” a phone call in which he solicited foreign interference in the 2020 presidential election. Any instance in which he lays claim to power he does not have should concern Americans, whether it is the authority to order military action against an Iranian official without congressional approval or “exclusive or preeminent responsibility and authority” over disease mitigation.

For a similar reason, his invitation to states to request major disaster declarations is somewhat troubling. Shoehorning a pandemic into the Stafford Act’s definition of “major disaster” is a stretch, at best. That definition includes “natural catastrophes,” which might seem to apply to the coronavirus, but it also clarifies that natural catastrophes include “any hurricane, tornado, storm, high water, winddriven water, tidal wave, tsunami, earthquake, volcanic eruption, landslide, mudslide, snowstorm, or drought”—a list that does not suggest Congress had disease outbreaks in mind. Trump is proposing to bend the law, no doubt to free up assistance that would only be available for major-disaster declarations. The ends might be worthy, but the means should give us pause.

One also must ask why he declared a national emergency under the NEA at all. The only power he invoked in that declaration was the Social Security Act waiver. But the Stafford Act declaration, in combination with the existing public-health emergency, also gives him access to the waiver provision—there was no need to issue both declarations. The move was quite possibly made for dramatic effect, to show he is taking the crisis seriously. As he put it so memorably in his news conference: “I’m officially declaring a national emergency. Two very big words.” But he also might be contemplating the invocation of additional national-emergency powers as the crisis progresses. That is not a comforting thought, given the breadth of powers available to him.

Finally, the president’s news conference raises an entirely different concern. The measures announced in the emergency declarations will help to bolster the capacity of hospitals. But they will do nothing to help slow the spread of the virus within communities—to “flatten the curve,” to use the now-familiar metaphor. Every public-health expert has emphasized the vital importance of social distancing. One of the most important tools at Trump’s disposal is the bully pulpit; yet in his press conferences to date, Trump has barely mentioned the concept of social distancing, let alone described what that entails and exhorted Americans to practice it. There are also serious questions about whether hospitals have sufficient access to needed equipment, including ventilators and protective gear for health workers. Trump has said nothing about that problem.

The fact is, Trump has been almost exclusively focused on keeping the virus out of our country through travel bans and quarantines, and has doubled down on this approach—extending travel bans and quarantines to a substantial list of European countries—long after the virus gained a foothold in the U.S. Bolstering the nation’s capacity to deal with the crisis inside our borders has never been a priority. According to reports, he was reluctant to declare emergencies under the Stafford Act and NEA. He feared they would undercut his message that the coronavirus is no worse than the seasonal flu—a message that is vital to his efforts to protect the markets and, in turn, his reelection prospects. In declaring the emergencies Friday, he was almost certainly bowing to pressure from the public and from his own administration’s health officials, not exhibiting a new attitude.

In that vein, people cannot forget that the president can invoke extremely potent authorities without declaring an emergency—powers that are more in line with his approach to date. Quarantines and travel bans are chief among these powers. Both represent a significant infringement on liberty, and while they might sometimes be necessary, the laws that authorize them lack key due-process protections and safeguards. Unlike the laws in some states, for instance, the law governing federal quarantine does not provide for judicial review of quarantine determinations.

Public-health experts are questioning the value of these measures at the current stage of the coronavirus pandemic. But Trump has always been drawn to strongman tactics and displays of power. Imposing travel bans and mandating quarantines are headline-grabbing acts that showcase the coercive powers of the president. As the election approaches and it becomes more important for Trump to appear aggressive in his response to the crisis, he will be even more likely to embrace measures that are showy and extreme—regardless of their effectiveness or their impact on individual rights.

The emergency powers that Trump has invoked are appropriate and will provide hospitals with some needed flexibility. But the country must pay close attention to what he does next, and be on guard for both emergency and nonemergency actions that go beyond what is needed or permitted by law. And Americans must recognize that the two very big words “national emergency” are not themselves an effective public-health strategy. The country will need much, much more in the coming months.